The compressor is the core component of a heat pump. It is the primary factor that determines whether the heat pump is good or bad. What counts is not merely the energy efficiency of the compressor but also the limits placed on applications by the evaporating and condensing temperatures, highly durable mechanical parts and quiet operation.

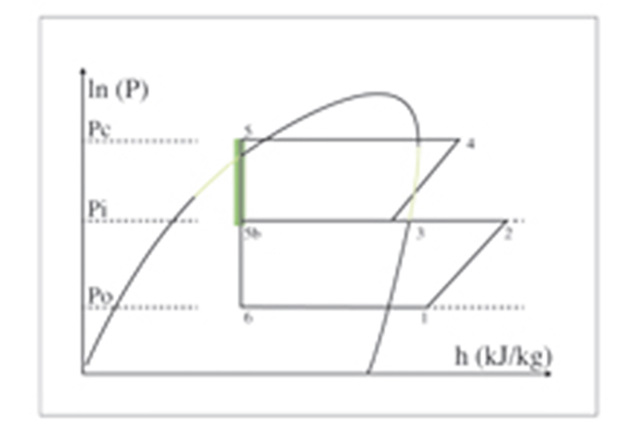

A compressor in a heat pump application operates in the same way as in a compression refrigeration plant. It conveys refrigerant in the form of vapour at low pressure and low temperature to a high pressure and high temperature stage. The motive force for this is generally an electric motor fed from the mains power grid and integrated into the compressor. “Electrically operated” is by no means a rarity in everyday life but it is not yet the standard for domestic heating. This sector offers a variety of diverse solutions, many of which burn fossil fuels such as oil and gas. Advantages other than efficiency are therefore important arguments, such as the fact that no oil tank is needed, and no gas connection (which will often be unobtainable, particularly in rural areas).

Selection

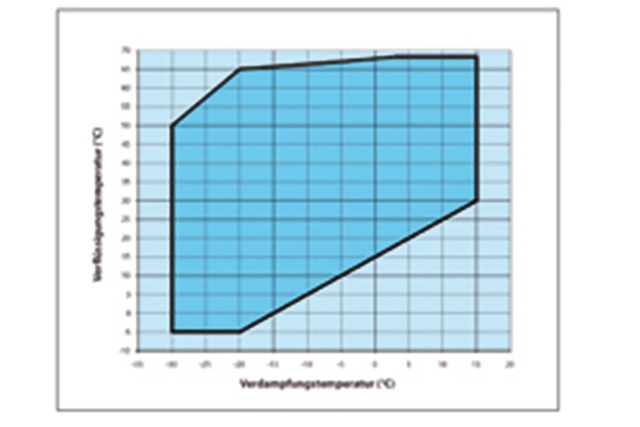

When selecting a heat pump compressor the first consideration is the refrigerant. The compressor must be approved for the desired refrigerant and must be usable for a wide range of applications corresponding to the current requirements. Any fluctuations in the temperature of the heat source over the course of a year will determine what evaporation temperatures will be required. For example, if the heat pump is to be used only during interseasonal periods – with some other form of heating, such as gas or oil, being used in winter – then the compressor will not need to be suitable for extremely low evaporation temperatures. Conversely, on the condenser side we then have to consider the necessary water supply temperature. A heat pump and an underfloor heating system thus constitute a perfect team. Underfloor heating systems do not need high inlet temperatures, hence only low condenser temperatures will be needed, which increases the efficiency of the heat pump. The worst possible case is when an old building’s heating system is brought up to date but its ancient cast-iron radiators are retained. These call for the highest input temperatures – by comparison, modern radiators are usually content with 10K lower. For cast-iron radiators in an old building the compressor needs to be geared for condenser temperatures of up to 65°C. Such systems do offer the additional assurance that, when (also) used to provide hot water they will not constitute a Legionella hazard. Temperatures higher than 60°C offer reliable protection from Legionella bacteria and the diseases they cause. Indeed, where large volumes of hot water are stored at temperatures lower than 60°C the water should be heated to 60°C at regular intervals. Manufacturers generally attempt to keep the compressor design as simple as possible, but where a very wide field of application is required it may be necessary to employ additional measures to ensure that the hot gas temperatures in the heat pump do not get too high.

Additional valves on the HHP